What every man needs to know

This guide to understanding the health of your prostate could save your life.

You may have been directed here by our leaflet. There is more information here than can be fitted in the leaflet.

We have tried to use common names rather than medical terms in this document to make it easy to understand.

What is your prostate?

The prostate is a gland which men have. It is in the lower abdomen just below the bladder. The prostate produces about 40% of your semen and combines that with the components produced by other organs, so it is necessary for fathering children. The pipe carrying pee from the bladder to the penis goes through the middle of the prostate.

Based on an image by Cancer Research UK / Wikimedia Commons

Trans-women and some intersex people also have a prostate, and this leaflet is relevant to them too.

What can go wrong with the Prostate?

There are 3 main things which can go wrong:

- Enlarged prostate, which happens to many men, from age 50 upwards.

- Prostatitis, which is inflammation of the prostate

- Prostate Cancer, which is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in in the UK.

Enlarged Prostate

Many men’s prostates never stop growing, and can start to cause problems from age 50 as they get larger due to narrowing of the pee pipe or pressing on the bladder. This is also known as BPH - benign prostatic hyperplasia. The size at which a prostate starts causing problems varies widely - some men with only slighly enlarged prostate might have probalems while other men with much larger prostates don't yet have any problems.

Enlarged prostate symptoms include:

Peeing more often, particularly more than once overnight.

- Difficult to start peeing, peeing slowly, straining to pee, taking a long time to finish peeing, or unable to pee at all.

If you are unable to pee, you must go to A&E immediately—this is a medical emergency. - A sudden need to pee and you can’t wait.

- Peeing small amounts, and a sense that you haven’t emptied when you finished peeing.

An enlarged prostate is not prostate cancer, but you can have both conditions which become a risk at around the same age. You should talk with your GP if you experience any of these symptoms, and it's also a good opportunity to ask for a PSA blood test (see Prostate Cancer below). Medications are available to help with the symptoms of an enlarged prostate. In severe cases, a common surgical procedure might be necessary.

Prostatitis

Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate. This can happen at any age from puberty. It is usually painful, but occasionally it has no symptoms. The pain may seem to come from somewhere else, such as the tip of the penis, balls (testicles), rectum, or lower back. It can also be painful if a doctor feels your prostate, during ejaculation, while peeing, or doing a poo.

Prostatis can be caused by a bacterial infection, although this rarely shows in urine or semen samples even when there is an infection. However, it often isn't a bacterial infection.

You should see your GP if you think you may have Prostatitis. However, prostatitis is sometimes difficult to treat and you may need referring to a prostatitis specialist at hospital.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate Cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the UK, yet there's no screening program such as those for breast cancer and bowel cancer (the second and third most commonly diagnosed cancers). It is very much the responsibility of each man to keep an eye out for their own health when it comes to prostate cancer. Over half prostate cancer diagnosis are at a late stage (T3 or T4), when the disease is more difficult to treat. The government had aimed to reduce this late diagnosis significantly, but the opposite has happened, particularly in the light of COVID interfering with many medical processes. In Luton, the figures are worse than the national average because men come forward for diagnosis later. This page will tell you what you need to know and how to reduce your risk of being diagnosed late.

You are welcome to contact us if you are concerned about prostate cancer. You can contact your GP, or the Prostate Cancer UK specialist nurses (see the External Links tab).

So when should you be concerned about Prostate Cancer?

There are two things to consider, your risk of getting prostate cancer, and any symptoms you have which could be related to prostate cancer.

Your risk of Prostate Cancer

Your risk of Prostate Cancer

We don't know what causes prostate cancer. For some cancers, what you eat, if you smoke, what you drink, and if you are overwieght can increase your risk of getting that cancer - these are said to be lifestyle cancers although lifestyle may have only a small effect in some cases. You can still get them if you have the perfect lifestyle, but the risk is lower.

Prostate Cancer is not a lifestyle cancer, or at least, we haven't yet learned what lifestyle factors might raise your risk. This means prostate cancer happens to many very healthy people, and it can be a significant surprise.

However, we do know a number of things that increase your risk of getting prostate cancer.

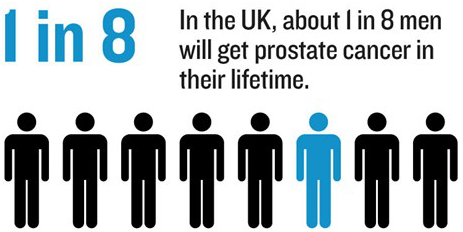

1 in 8 men will get significant prostate cancer during their lives. The rate is increasing and in men born from 1960, this figure is probably 1 in 6 men.

1 in 8 men will get significant prostate cancer during their lives. The rate is increasing and in men born from 1960, this figure is probably 1 in 6 men.- The incidence of prostate cancer increases with age, and so men from age 50 are considered more at risk and this increases as you get older. It does also happen in men below 50.

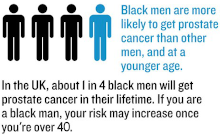

- Black African and Black Caribbean men have twice the risk of prostate cancer, and they often get it at a younger age and more aggressively, so they are considered at risk from age 40.

- If your father or brother had prostate cancer, you have twice the chance of getting it yourself.

- If your mother or sister had breast or ovarian cancer below age 60, your chance of getting prostate cancer is increased.

Symptoms of Prostate Cancer

The most common symptom of prostate cancer is nothing - no symptoms at all, particularly in the early stages, but sometimes in late stage too. This means you mustn't assume you don't have prostate cancer just because you have no symptoms - you still need to consider your risk.

There are some symptoms which could suggest prostate cancer as a possible cause. However, they are all more commonly symptoms of something else, so there is no symptom from which you can easily identify prostate cancer. If you have any of these symptoms, you do need to be investigated though, to be sure it's not prostate cancer (or some other potentially serious cause).

- Problems getting erections or weaker erections.

- Significant reduction or loss of semen.

- Blood in pee or semen.

- Pain in the back, ribs, pelvis/groin, other bones.

- Unexpected weight loss

It is worth repeating that all of these symptoms are more commonly caused by other things, but they can be caused by prostate cancer, so you do need to get yourself checked out if you have any of these.

Many GPs still regard problems with peeing as prostate cancer symptoms which means that you are more likely to get a PSA blood test if you have symptoms of an enlarged prostate. However, this also means some GPs refuse to do a PSA blood test if you have no symptoms. Yet most men diagnosed with prostate cancer (certanly while it's still potentially curable) have no symptoms of the prostate cancer.

The following paper goes in to this in some detail:

Urinary symptoms and prostate cancer—the misconception that may be preventing earlier presentation and better survival outcomes

Other trials such as ProtecT also showed no link between problems peeing and prostate cancer.

So, how do I get checked?

If you have any of the risk factors or any symptoms, you should get checked. You should consider getting checked even if you don't.

In the first instance, make an appointment with your GP. Talk to your GP about your risk and your symptoms, or just your concerns. The GP can order a PSA blood test. This tests how much of the chemical the prostate makes, PSA, is leaking into the blood stream. Around 85% of prostate cancers cause extra PSA to be leaked into the blood. While PSA tests are very accurate measures of PSA, many results are in a wide range which doesn't tell you if you have prostate cancer, but indicates you need to be checked further, in which case you would be referred to hospital for an MRI scan in the first instance. A PSA test can never tell you that you don't have prostate cancer, because about 15% of prostate cancers don't generate a raised PSA level.

In the first instance, make an appointment with your GP. Talk to your GP about your risk and your symptoms, or just your concerns. The GP can order a PSA blood test. This tests how much of the chemical the prostate makes, PSA, is leaking into the blood stream. Around 85% of prostate cancers cause extra PSA to be leaked into the blood. While PSA tests are very accurate measures of PSA, many results are in a wide range which doesn't tell you if you have prostate cancer, but indicates you need to be checked further, in which case you would be referred to hospital for an MRI scan in the first instance. A PSA test can never tell you that you don't have prostate cancer, because about 15% of prostate cancers don't generate a raised PSA level.

Another check your doctor can do is to feel your prostate. Prostate cancer can sometimes be felt on the prostate, but it's not always in a location which can be felt. The doctor might also identify that you have an enlarged prostate (which is unrelated to prostate cancer) and might be the cause of some of your symptoms which can often be easily treated with medication.

Some doctors are concerned that getting checked might start you down a path of prostate cancer investigation which ultimately results in you being given the all-clear after many anxious weeks and tests, or even that you may end up being treated for prostate cancer when it could have been left alone and never had any impact on you (known as over treatment). This used to be a significant issue when diagnostic processes were much more primitive than they are today, but there is probably still a small amount of over treatment, estimated at around 4%. Some GPs still think of when this figure was much higher over 10 years ago. On the other hand, with over 50% of cases being diagnosed late, it would seem that we are not testing often enough, early enough. Never allow yourself to be persuaded not to have a PSA test just because you have no symptoms - most men diagnosed with significant prostate cancer have no symptoms of the cancer.

You should also consider asking for periodic PSA tests, because the rate of change of PSA levels over time is a much more useful indication of prostate cancer than the actual value of a single test. The test interval might be anywhere between 1 and 3 yearly, depending what the level is and the rate of change of previous readings.

If you struggle to get a PSA test from your GP, you can do one by post if you're up to using a finger pricker and collecting a small sample of your own blood (just under 1cc, or about 15 drips). At the time of writing, this costs £29 and returns a result to 2 decimal places, and an interpretation of the result, based on the value, your age, and the rate of change if you've done previous PSA tests using the service, and what to do next. Some local charities also offer PSA tests from time to time. If you are interested in using postal or local charity testing, you start by registering at https://mypsatests.org.uk/ and you can look at the list of community testing events or order a postal test.

If you struggle to get a PSA test from your GP, you can do one by post if you're up to using a finger pricker and collecting a small sample of your own blood (just under 1cc, or about 15 drips). At the time of writing, this costs £29 and returns a result to 2 decimal places, and an interpretation of the result, based on the value, your age, and the rate of change if you've done previous PSA tests using the service, and what to do next. Some local charities also offer PSA tests from time to time. If you are interested in using postal or local charity testing, you start by registering at https://mypsatests.org.uk/ and you can look at the list of community testing events or order a postal test.

The following might cause a temporary rise in PSA and are best avoided before a PSA blood test:

- Ejaculating in the previous 48 hours

- Cycling or horse riding in the previous 48 hours

- Some forms of strenuous exercise in the previous 48 hours

- Having COVID in the previous month

Variation of Serum PSA Levels in COVID-19 Infected Male Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH): A Prospective Cohort Studys - Having a COVID vaccination in the previous month

PSA Thresholds

There's no one agreed set of PSA thresholds, and lots of sets of different values are in use.

NHS England recommends for men without symptoms:

A PSA threshold of 3.0, regardless of age.

A PSA threshold of 3.0 is also used as the threshold for eligibility for referral to the Rapid Protocol at Imperial, and is the proposed threshold under the TRANSFORM trial. 3.0 is also the threshold used in much of the EU.

NICE (NHS England) recommends for men with symptoms:

| Age | PSA |

| Below 40 | Use clinical judgement |

| 40-49 | More than 2.5 |

| 50-59 | More than 3.5 |

| 60-69 | More than 4.5 |

| 70-79 | More than 6.5 |

| Above 79 | Use clinical judgement |

Urologists sometimes use the BAUS (British Association or Urological Surgeons) recommendations:

| Age | PSA |

| 40-49 | More than 2.7 |

| 50-59 | More than 3.9 |

| 60-69 | More than 5.0 |

| 70-79 | More than 7.2 |

| 80-84 | More than 10 |

| 85+ | More than 20 |

Borderline results should be retested in 3 months before referral.

CHAPS uses the following thresholds for men without symptoms, which have been worked out from research into screening using PSA testing. These levels are roughly in between the NICE and BAUS recommended levels:

CHAPS also recommends stratified retest intervals depending on the last test result and the man's risk, based on their PSA base screening tests.

The NICE and BAUS figures are specified for men with symptoms (pretty meaningless given current research shows most men diagnosed have no symptoms). The CHAPS and NHS England figures are for screening men, and hence for men without symptoms. We use the CHAPS figures in the leaflet, but your doctor may use one of the other recommendations.

Some sets of recommendations also suggest referral if your PSA increases by more than a certain percentage per year (such as 20%) even if you are still below the age threshold, although NICE, BAUS, and CHAPS don't cover this case.

How often should I be tested?

You should also consider asking for periodic PSA blood tests, because prostate cancer can appear in the future, even if your current test result is OK. The maximum suggested test interval can be anywhere between 1 and 3 years, depending on what the level is, and your other risk factors.

| Slightly Raised PSA (in amber range) | 3 months* |

| Immediate family history, or Black African or Black Caribbean, or PSA in upper 25% of normal range |

1 year |

| No immediate family history, and PSA in 50-74% of normal range |

2 years |

| No enhanced risk factors, and PSA in 0-50% of normal range |

3 years |

| No enhanced risk factors, and Age > 75 and PSA ≤ 1ng/ml Age > 80 and PSA ≤ 50% normal range |

No more PSA testing required |

*Retest, and investigate if situation has not resolved.

These retest intervals are as recommended by CHAPS, based on their experience of screening men using PSA blood testing.

If you are diagnosed

If you are unfortunately diagnosed with prostate cancer or another prostate problem, please do give us a call for a chat. It can help to talk with people who’ve been there already – you are not alone.

📞 01252 237550

Don't forget you are welcome to contact us if you have any questions.